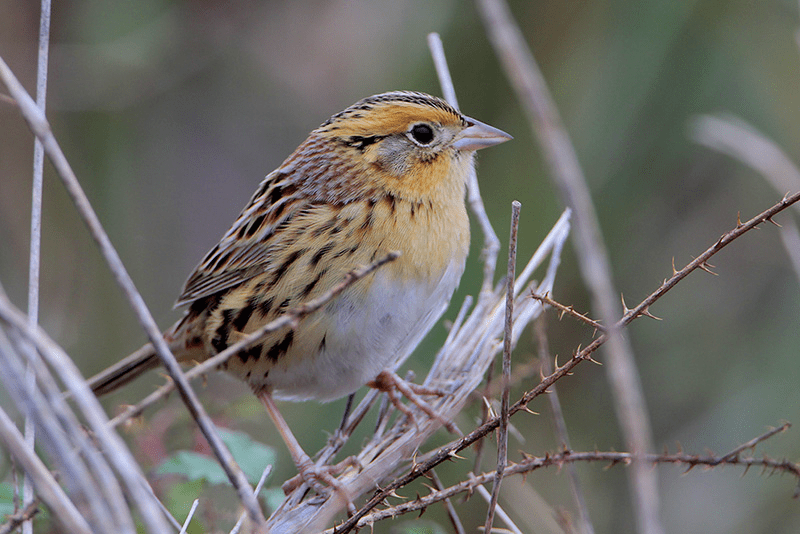

LeConte’s Sparrow (Ammospiza leconteii)

Family: Passerellidae

By Robert Buckert, Houston Audubon Coastal Conservation Technician

This week’s beak belongs to one of the most secretive grassland songbirds in North America. Some birders associate late fall birding with sparrows, as most arrive and are prominent in this window after many other songbirds have already passed through. This species is in a similar vein to my recently posted Black Rail, sharing a reputation for grassy secrecy and a furtive lifestyle. Tiny, warm-toned, and notoriously skulky, the LeConte’s Sparrow is a jewel of the winter prairie, delightfully patterned yet remarkably difficult to see well. These shy sparrows hug the ground beneath dense grasses, freezing in place or slipping between stems like little feathered field mice. Even seasoned birders know the drill: you don’t so much see a LeConte’s Sparrow as you catch a flicker of orange and buff disappearing into the tangle.

LeConte’s Sparrows are among our smallest sparrows, just 5 inches long, with a beautifully crisp facial pattern—rich pumpkin-spice-orange cheeks and crown sides, a grayish nape flecked with pink and black, and a narrow pale median crown stripe. Their flanks are boldly streaked, while the breast is soft and buffy, contributing to their “warm” look. This elegant coloration blends perfectly with the winter grasses they depend on. Their short, sharp bills are built for gleaning insects, tiny seeds, and other fine plant material, which they forage for quietly on the ground.

During the breeding season in the northern prairies and peatlands, males sing a surprisingly mechanical, insect-like song – an opening buzz followed by a few soft ticks – that carries only a short distance. This understated vocal performance mirrors their overall personality: unobtrusive, gentle, and happiest when hidden. Their nests, tucked low within clumps of sedges or grasses, cradle 3–5 eggs that hatch into downy young ready to leave after just over a week. Despite widespread interest, much of their life history is still poorly understood due to their retiring behavior and preference for dense, difficult habitats.

Here on the Upper Texas Coast, LeConte’s Sparrows are winter visitors, favoring wet prairies, overgrown fields, coastal grasslands, and the edges of marshes. At places like Bolivar Flats, Frenchtown Road, and other grassy corners of the peninsula, they slip quietly through the vegetation from October into April. Detection is best at dawn or on calm days when they are less apt to flush long distances. A gentle, patient walk through suitable habitat may produce one sitting tight until the last possible moment—before zipping away low and fast with legs dangling, their distinctive escape signature.

The species breeds primarily across the northern Great Plains and southern boreal Canada and winters across the Gulf Coast and Southeast. Habitat loss in both breeding and wintering ranges—especially the conversion of native prairie to agriculture or development—poses ongoing and pressing concerns. Though still considered fairly common, local declines have been noted where grasslands have been reduced or poorly managed. Conservation of native prairies, wet meadows, and coastal grasslands remains essential to the future of this charismatic species.

If you’re lucky enough to spot a LeConte’s Sparrow this winter, take a moment to appreciate just how special the encounter is. These petite beauties are masters of staying unseen, but when they do reveal themselves, even briefly, their exquisite plumage and quiet demeanor leave a lasting impression—another reminder of the richness and subtlety of our coastal prairie mosaic.

Visit our Bird Gallery to read about other Texas birds!